The 'Stock' Exchange

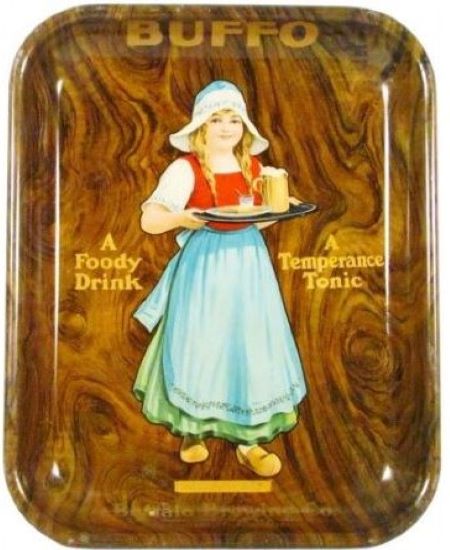

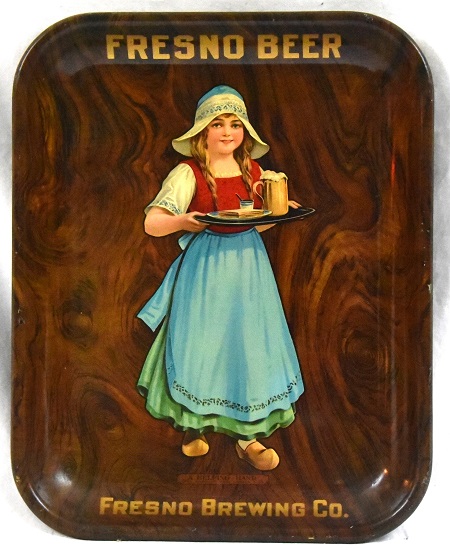

American Art Works: No. 139 "A Helping Hand"

American Art Works: No. 139 "A Helping Hand"

Date: 1914 to 1920

Size: 10.5" x 13.25"

Type: Pie

Scarcity: Common

Value: $$ to $$$

Condition & Brewer Dependent

Size: 10.5" x 13.25"

Type: Pie

Scarcity: Common

Value: $$ to $$$

Condition & Brewer Dependent

General Comments

We’d never thought about this tray or any of the woodgrain trays as being examples of trompe l’oiel until discussing the concept for the preceding design (“The Connoisseur” No. 138), but the entire effect is to give the impression that the tray itself is made out of wood. Reflecting back on the Meek/American Art Works catalog, the faux marquetry of “San Toy” (No. 114) and “Yama, Yama” (No. 115), as well as the faux lacquerware look of the “japaned” design (No. 59, No. 83, and No. 94) also fall in this category.

The girl is clearly attired in what is intended to be a traditional Dutch outfit with the wooden shoes being a clear give-away. We believe this is due to a confusion over “Duetsch” the German word for Germa,n with Dutch, a term that refers to the language spoken in the Netherlands. This can be blamed on the ignorance of the British, who back in the day, used to refer to anyone who spoke a Germanic language as "Deutsch" (which is ironic, since English itself is a Germanic language!). Over time, "Deutsch" gradually morphed into "Dutch", which was used to refer to people from both the highlands that make up present-day Germany, and the lowlands that make up the present-day Netherlands. The English ignorance of the difference between Dutch and German people still resonates even today, as we can see in the case of the “Pennsylvania Dutch” settlers in the United States, who are actually Germanic migrants.

It is unclear where this girl is being “a helping hand.” It is shocking to modern sensibilities to think that it could be anywhere other than in the home where she is bringing a sandwich and beer to her father or other male relatives. However, American attitudes toward children and child labor where quite different in the late 19th and early 20th century which was a time in this country when young children routinely worked legally. As industry grew in the period following the Civil War, children, often as young as 10 years old, but sometimes much younger, labored. They not only worked in industrial settings, but also in retail stores, on the streets, on farms, and in home-based industries.

We’d never thought about this tray or any of the woodgrain trays as being examples of trompe l’oiel until discussing the concept for the preceding design (“The Connoisseur” No. 138), but the entire effect is to give the impression that the tray itself is made out of wood. Reflecting back on the Meek/American Art Works catalog, the faux marquetry of “San Toy” (No. 114) and “Yama, Yama” (No. 115), as well as the faux lacquerware look of the “japaned” design (No. 59, No. 83, and No. 94) also fall in this category.

The girl is clearly attired in what is intended to be a traditional Dutch outfit with the wooden shoes being a clear give-away. We believe this is due to a confusion over “Duetsch” the German word for Germa,n with Dutch, a term that refers to the language spoken in the Netherlands. This can be blamed on the ignorance of the British, who back in the day, used to refer to anyone who spoke a Germanic language as "Deutsch" (which is ironic, since English itself is a Germanic language!). Over time, "Deutsch" gradually morphed into "Dutch", which was used to refer to people from both the highlands that make up present-day Germany, and the lowlands that make up the present-day Netherlands. The English ignorance of the difference between Dutch and German people still resonates even today, as we can see in the case of the “Pennsylvania Dutch” settlers in the United States, who are actually Germanic migrants.

It is unclear where this girl is being “a helping hand.” It is shocking to modern sensibilities to think that it could be anywhere other than in the home where she is bringing a sandwich and beer to her father or other male relatives. However, American attitudes toward children and child labor where quite different in the late 19th and early 20th century which was a time in this country when young children routinely worked legally. As industry grew in the period following the Civil War, children, often as young as 10 years old, but sometimes much younger, labored. They not only worked in industrial settings, but also in retail stores, on the streets, on farms, and in home-based industries.

In the 18th century, the arrival of a newborn to a rural family was viewed by the parents as a future beneficial laborer and an insurance policy for old age. At an age as young as 5, a child was expected to help with farm work and other household chores. The agrarian lifestyle common in America required large quantities of hard work, whether it was planting crops, feeding chickens, or mending fences. Large families with less work than children would often send children to another household that could employ them as a maid, servant, or plowboy. Colonial laws modeled after British laws sought to prevent children from becoming a burden on society. Sometimes the primary motivation in employing children was not about preventing their idleness, but rather about satisfying commercial interests and the desire to settle the vast American continent. Regardless of the motivation, a successful childhood was seen as one that developed the child’s productive capacity. In many towns, mills and glass factories regularly employed girls and boys whose smaller hands made them ideal for certain tasks.

Annual reports from the Ohio Department of Inspection of Workshops, Factories and Public Buildings routinely reported the number of children employed in the factories of Meek & Beach/Meek/American Art Works, and there are passing references in various newspaper accounts of the time as well. In fact, there is a labor agreement following a 1901 strike (involving both Meek & Beach, as well as Novelty Advertising) by members of Federal Labor Union 8170 and Ladies Federal Labor Union 8405 that specifically calls out the wages paid to boys and girls ($2-$4 a week) and proposed increases. Not only was this reported in the Annual report for 1901 made to the Seventy-Fifth General Assembly of the State of Ohio, but in various labor and trade journals of the time.

At the time, regulation of child labor was left to the individual states and from 1902-1915 child labor committees, as part of the early 20th century progressive reform movement pushed reforms at the state level; however, many southern states resisted. Organizers were successful in getting Congress to pass Federal Child Labor Laws in 1916 and 1918, but the Supreme Court declared the unconstitutional. A Constitutional amendment was passed in 1924, but individual states were not keen to rarify it due to opposition from farm and church organizations who feared increased Federal power over children. The codes developed under the National Industrial Recovery Act initially served to reduce child labor, but permanent restrictions were not put in place until the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

Sahling does have an entry in his workbook from January 1914 for “A Helping Hand, stock tray.”

Size, Shape and Advertising Placement

Every tray example we’ve seen of this design has been a small oblong, and unlike the similar “San Toy” (No.114) and “Yama Yama” (No.115) which also appeared frequently as signs, we have only seen a single tin-over-cardboard example of “A Helping Hand” from Knapstein Brewing of New London, WI. The underlying woodgrain design is continuous from the face of the tray to the edge; in previous examples like “San Toy” there was a separate woodgrain pattern that made up the rim, almost like a frame or border. Advertising text is gold and primarily occurs on the rim; however, secondary text and logos sometimes appear on the face of the tray.

Hager & Price

Hager had stopped commenting on individual trays after No. 136, but he does include this design in his date of introduction table (1914) and in his catalog. This was a particularly popular design among brewers and allied trades, but it is far less common to find non-brewery examples. Given this it’s hard to find examples, even in very good to excellent examples that reach much more than the low three figures, with prices falling off steeply for lower grades.

Annual reports from the Ohio Department of Inspection of Workshops, Factories and Public Buildings routinely reported the number of children employed in the factories of Meek & Beach/Meek/American Art Works, and there are passing references in various newspaper accounts of the time as well. In fact, there is a labor agreement following a 1901 strike (involving both Meek & Beach, as well as Novelty Advertising) by members of Federal Labor Union 8170 and Ladies Federal Labor Union 8405 that specifically calls out the wages paid to boys and girls ($2-$4 a week) and proposed increases. Not only was this reported in the Annual report for 1901 made to the Seventy-Fifth General Assembly of the State of Ohio, but in various labor and trade journals of the time.

At the time, regulation of child labor was left to the individual states and from 1902-1915 child labor committees, as part of the early 20th century progressive reform movement pushed reforms at the state level; however, many southern states resisted. Organizers were successful in getting Congress to pass Federal Child Labor Laws in 1916 and 1918, but the Supreme Court declared the unconstitutional. A Constitutional amendment was passed in 1924, but individual states were not keen to rarify it due to opposition from farm and church organizations who feared increased Federal power over children. The codes developed under the National Industrial Recovery Act initially served to reduce child labor, but permanent restrictions were not put in place until the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

Sahling does have an entry in his workbook from January 1914 for “A Helping Hand, stock tray.”

Size, Shape and Advertising Placement

Every tray example we’ve seen of this design has been a small oblong, and unlike the similar “San Toy” (No.114) and “Yama Yama” (No.115) which also appeared frequently as signs, we have only seen a single tin-over-cardboard example of “A Helping Hand” from Knapstein Brewing of New London, WI. The underlying woodgrain design is continuous from the face of the tray to the edge; in previous examples like “San Toy” there was a separate woodgrain pattern that made up the rim, almost like a frame or border. Advertising text is gold and primarily occurs on the rim; however, secondary text and logos sometimes appear on the face of the tray.

Hager & Price

Hager had stopped commenting on individual trays after No. 136, but he does include this design in his date of introduction table (1914) and in his catalog. This was a particularly popular design among brewers and allied trades, but it is far less common to find non-brewery examples. Given this it’s hard to find examples, even in very good to excellent examples that reach much more than the low three figures, with prices falling off steeply for lower grades.

Non-Beer Related & Non-Tray Uses

Confirmed Brewer used Stock Trays

Click the Picture to Return to Meek & Beach Stock Catalog Page