The 'Stock' Exchange

American Art Works: No. 154

American Art Works: No. 154

Date: 1925 - 1930

Size: 13.5" x 13.5"

Type: Pie

Scarcity: Very Rare

Value: $$$ to $$$

Condition & Brewer Dependent

Size: 13.5" x 13.5"

Type: Pie

Scarcity: Very Rare

Value: $$$ to $$$

Condition & Brewer Dependent

General Comments

It is unclear who was the intended market for this design. Although we do not have copyright or production data from Sahling to definitively date it, it appears well into the prohibition era, coming after several trays, including No. 151 which is the last dated tray (1925). It also comes before a couple more ice cream designs (No. 155 and 156) before beer related designs (like the revised version of No. 156 where the ice cream is replaced with a glass of beer). The design is a more contemporary “pretty lady” in the 1920s “flapper” style that’s too risqué for ice cream manufacturers and small retailers given the lifestyle it implies.

Flappers of the 1920s were young women known for their energetic freedom, embracing a lifestyle viewed by many at the time as outrageous, immoral or downright dangerous. Now considered the first generation of independent American women, flappers pushed barriers in economic, political and sexual freedom for women. Multiple factors—political, cultural and technological—led to the rise of the flappers.

It is unclear who was the intended market for this design. Although we do not have copyright or production data from Sahling to definitively date it, it appears well into the prohibition era, coming after several trays, including No. 151 which is the last dated tray (1925). It also comes before a couple more ice cream designs (No. 155 and 156) before beer related designs (like the revised version of No. 156 where the ice cream is replaced with a glass of beer). The design is a more contemporary “pretty lady” in the 1920s “flapper” style that’s too risqué for ice cream manufacturers and small retailers given the lifestyle it implies.

Flappers of the 1920s were young women known for their energetic freedom, embracing a lifestyle viewed by many at the time as outrageous, immoral or downright dangerous. Now considered the first generation of independent American women, flappers pushed barriers in economic, political and sexual freedom for women. Multiple factors—political, cultural and technological—led to the rise of the flappers.

During World War I, women entered the workforce in large numbers, receiving higher wages that many working women were not inclined to give up during peacetime. In August 1920, women’s independence took another step forward with the passage of the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote. And in the early 1920s, Margaret Sanger made strides in providing contraception to women, sparking a wave of women’s rights to birth control. The 1920s also brought about Prohibition, the result of the 18th Amendment ending legal alcohol sales. Combined with an explosion of popularity for jazz music and jazz clubs, the stage was set for speakeasies, which offered illegally produced and distributed alcohol.

Henry Ford’s mass production of cars brought down automobile prices, allowing the younger generation far more mobility than in earlier eras. Many people, a number of them young women, drove these cars into cities, which experienced a population boom. With all these pieces in place, an unprecedented social explosion for young women was all but inevitable.

No one knows how the word flapper entered American slang, but its usage first appeared just following World War I. The classic image of a flapper is that of a stylish young party girl. Flappers smoked in public, drank alcohol, danced at jazz clubs and practiced a sexual freedom that shocked the Victorian morality of their parents. They donned fashionable flapper dresses of shorter, calf-revealing lengths and lower necklines like the young lady depicted, though not typically form fitting: Straight and slim was the preferred silhouette. Flappers wore high heel shoes and threw away their corsets in favor of bras and lingerie. They gleefully applied rouge, lipstick, mascara and other cosmetics, and favored shorter hairstyles like the bob—many of which the design depicts.

Henry Ford’s mass production of cars brought down automobile prices, allowing the younger generation far more mobility than in earlier eras. Many people, a number of them young women, drove these cars into cities, which experienced a population boom. With all these pieces in place, an unprecedented social explosion for young women was all but inevitable.

No one knows how the word flapper entered American slang, but its usage first appeared just following World War I. The classic image of a flapper is that of a stylish young party girl. Flappers smoked in public, drank alcohol, danced at jazz clubs and practiced a sexual freedom that shocked the Victorian morality of their parents. They donned fashionable flapper dresses of shorter, calf-revealing lengths and lower necklines like the young lady depicted, though not typically form fitting: Straight and slim was the preferred silhouette. Flappers wore high heel shoes and threw away their corsets in favor of bras and lingerie. They gleefully applied rouge, lipstick, mascara and other cosmetics, and favored shorter hairstyles like the bob—many of which the design depicts.

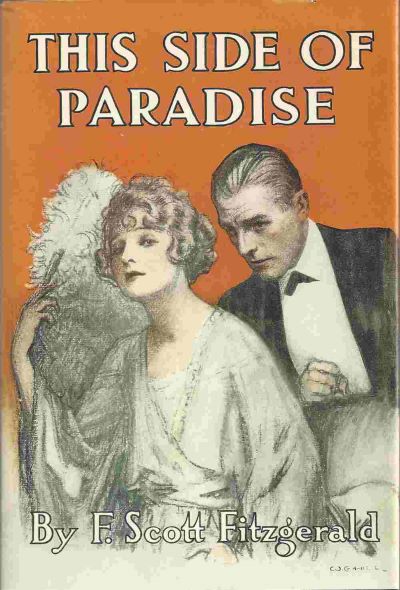

Author F. Scott Fitzgerald was credited by the press of the time as the creator of the flapper because of his debut novel, “This Side of Paradise,” though the book didn’t specifically mention flappers. The credit stuck and Fitzgerald began to write about flapper culture in short stories for the Saturday Evening Post in 1920, opening up the Jazz Age lifestyle to middle-class homes. A collection of these stories was published that year under the title “Flappers and Philosophers,” cementing Fitzgerald as the flapper expert for the next decade. In modern minds, the association is mostly with his most famous novel, The Great Gatsby especially because of recent film adaptations.

The credit stuck and Fitzgerald began to write about flapper culture in short stories for the Saturday Evening Post in 1920, opening up the Jazz Age lifestyle to middle-class homes. A collection of these stories was published that year under the title “Flappers and Philosophers,” cementing Fitzgerald as the flapper expert for the next decade. In modern minds, the association is mostly with his most famous novel, The Great Gatsby especially because of recent film adaptations.

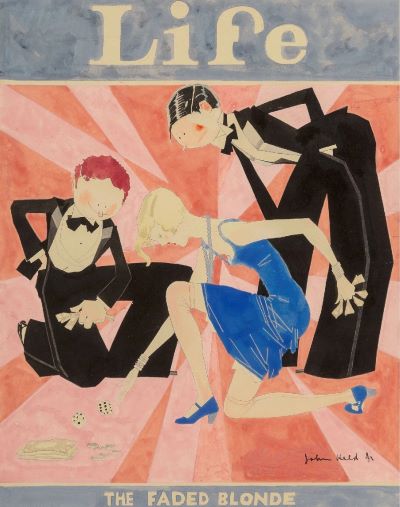

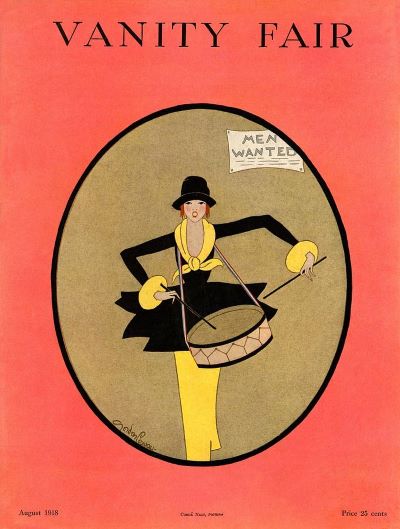

Recognizing that women now had disposable incomes of their own, advertising courted their interests beyond household items. Soap, perfume, cosmetics, cigarettes and fashion accessories were all the subjects of ads targeting women. Helen Lansdowne Resor was the most powerful woman in advertising at the time. The head of women’s advertising at the J. Walter Thompson Agency, she worked her way up from secretary thanks to her keen understanding of selling to women. She was the first advertising executive to push sex appeal as a method of marketing to women, often focused on getting male attention. Flapper style regularly graced the covers of magazines like Vanity Fair and Life, drawn by artists like John Held and Gordon Conway.

Recognizing that women now had disposable incomes of their own, advertising courted their interests beyond household items. Soap, perfume, cosmetics, cigarettes and fashion accessories were all the subjects of ads targeting women. Helen Lansdowne Resor was the most powerful woman in advertising at the time. The head of women’s advertising at the J. Walter Thompson Agency, she worked her way up from secretary thanks to her keen understanding of selling to women. She was the first advertising executive to push sex appeal as a method of marketing to women, often focused on getting male attention. Flapper style regularly graced the covers of magazines like Vanity Fair and Life, drawn by artists like John Held and Gordon Conway.

Artist: John Held

Artist: Gordon Conway

Not everyone was a fan of women’s newfound sexual freedom and consumer ethos, and there was inevitably a public reaction against flappers. Utah attempted to pass legislation on the length of women’s skirts. Virginia tried to ban any dress that revealed too much of a woman’s throat and Ohio tried to ban form-fitting outfits. Women who populated beaches in bathing suits that were deemed inappropriate were escorted off the beach by police or arrested if they refused. Clergymen like Rabbi Stephen S. Wise and Baptist pastor Dr. John Roach Straton became known for their tirades against young women’s fashions. Flappers also received the criticism of women’s rights activists like Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Lillian Symes, who felt flappers had gone too far in their embrace of licentiousness.

The age of the flapper came tumbling down suddenly on October 29, 1929, with the stock market crash and the beginning of the Great Depression. No one could afford the lifestyle any longer, and the new era of frugality made the freewheeling hedonism of the Roaring Twenties seem wildly out of touch with grim new economic realities. Many film-star flappers had already met their end two years earlier with the advent of talking films, which was not always kind to them. The Hays Code in 1930, which severely limited sexual themes in movies, made independent women in the flapper mold almost impossible to portray onscreen.

Sahling's Design Notes

By this time Sahling had left the Art Department and there are no further entries in his workbook.

Size, Shape and Message Placement

We have only seen this design twice, both of which were 13” concave pie trays. Both were stock samples with black rims but without advertising; we imagine it would have appeared in gold text on the rim.

Hager & Price

Hager does not have any designs beyond “When Dreams Come True” (No. 150), but even if he did, we would not be surprised if this design was not included given its scarcity. We have only seen this for sale once (the other example was in a private collection) and the slightly below average condition stock sample sold in the high double figures.

The age of the flapper came tumbling down suddenly on October 29, 1929, with the stock market crash and the beginning of the Great Depression. No one could afford the lifestyle any longer, and the new era of frugality made the freewheeling hedonism of the Roaring Twenties seem wildly out of touch with grim new economic realities. Many film-star flappers had already met their end two years earlier with the advent of talking films, which was not always kind to them. The Hays Code in 1930, which severely limited sexual themes in movies, made independent women in the flapper mold almost impossible to portray onscreen.

Sahling's Design Notes

By this time Sahling had left the Art Department and there are no further entries in his workbook.

Size, Shape and Message Placement

We have only seen this design twice, both of which were 13” concave pie trays. Both were stock samples with black rims but without advertising; we imagine it would have appeared in gold text on the rim.

Hager & Price

Hager does not have any designs beyond “When Dreams Come True” (No. 150), but even if he did, we would not be surprised if this design was not included given its scarcity. We have only seen this for sale once (the other example was in a private collection) and the slightly below average condition stock sample sold in the high double figures.

Confirmed Brewer used Stock Trays

Non-Beer Related & Non-Tray Uses

Click the Picture to Return to Meek & Beach Stock Catalog Page